A quite afternoon. A gallery. Staring at an old Renaissance masterpiece. Maybe it’s a Caravaggio or a Vermeer. The faces are illuminated with a divine glow, the shadows seem to hold secrets, and every detail— every fold of fabric or twist of a hand—seems deliberate. You’re transported to another time, another story.

Now imagine that same feeling while looking at a photograph from a protest, a war zone, or the eyes of a refugee girl in Afghanistan. Documentary photography, when done right, carries that same weight, that same timeless quality. And much of it, knowingly or not, owes a debt to Renaissance art

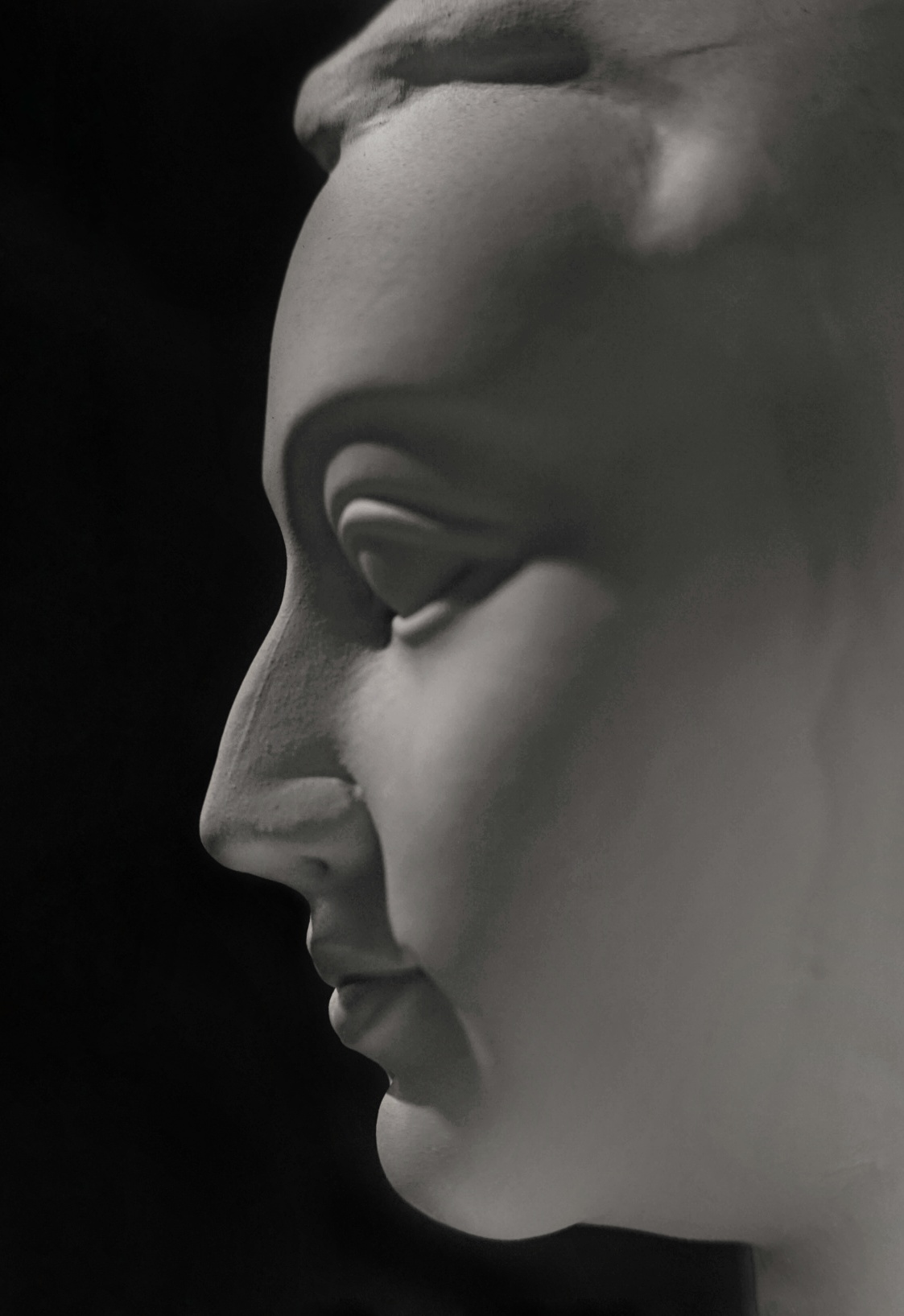

The Renaissance didn’t invent light, but it gave it a voice. Artists like Rembrandt and Caravaggio mastered chiaroscuro, the stark contrast between light and dark, not just as a technique but as a tool for storytelling. The way light fell on a subject wasn’t arbitrary; it was intentional, guiding the viewer to the heart of the story. In documentary photography, light still speaks volumes. Think of Dorothea Lange’s Migrant Mother, where the interplay of natural light and shadow frames a woman’s weary expression, or James Nachtwey’s war photography, where light often feels like the last remnant of hope in otherwise desolate scenes. These images echo Renaissance works by showing us not just what happened, but how it felt.

Renaissance artists were architects of the canvas. They used the golden ratio and symmetrical balance to create compositions that were visually harmonious yet emotionally compelling. Take Raphael’s The School of Athens. The geometry of the painting isn’t just pleasing to the eye; it subtly guides you to its intellectual and emotional core. Documentary photographers use similar strategies. The careful framing of subjects in historical events, like the lone man standing in front of tanks at Tiananmen Square or the iconic raising of the flag at Iwo Jima, borrows from this legacy. The placement of elements in the frame is never accidental— it’s an unspoken dialogue between the photographer and the viewer, rooted in centuries-old techniques.

Renaissance art loved its symbols. A skull on a table hinted at mortality, a dog at someone’s feet symbolized loyalty, a fruit bowl hinted at abundance—or temptation. Every detail was deliberate, weaving layers of meaning into a single frame. This tradition finds its way into documentary photography too. A single raised fist in a crowd becomes a symbol of resistance. A broken clock in the rubble of a bombed-out city captures the fragility of time. Photographers often use these visual cues to tell stories that words cannot—drawing on the Renaissance belief that the viewer must participate in uncovering the meaning.

What ties Renaissance art and contemporary documentary photography together is their shared mission: to make us see. Both forms invite us to pause, to reflect, and to engage with the world in a deeper way. They remind us that light is not just illumination but revelation, that composition is not just structure but meaning, and that art—whether painted on a canvas or captured in a photograph—is always about the human story.

So, the next time you look at a photograph of a moment in history, notice the light, the balance, the details. And remember, you’re not just seeing a snapshot of time—you’re witnessing a legacy, centuries in the making.

Let me know in the comments what do you think!